Got to look into this. ART:21

Posts Tagged ‘the arts’

ART:21

Posted in art, technology, tagged art, Laurie Anderson, media, the arts on 04/19/2010|

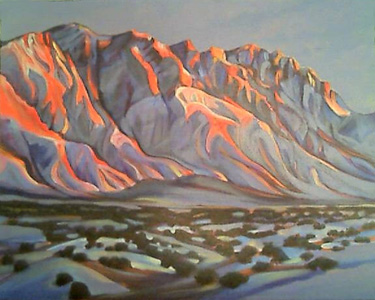

Sandias Twilight painting

Posted in art, tagged drawing, fine art, oil painting, Southwest, the arts on 04/13/2010| Leave a Comment »

The American Southwest landscape has always appealed to me. The play of light as sun and shadows pass over the contrasting textures provides new inspiration every time. This is an 18″ X 24″ piece.

art pages

Posted in Random thoughts, tagged drawing, inspiration, style, the arts on 04/13/2010| Leave a Comment »

Gene Matras pen and ink illustration work

Aphelion Art scratchboard works by Cathy Sheeter

3Kicks Fine Art Studios by Matt Marchant

“morning drawings” by Gabriela Vainsencher

“One hundred awesome paintings in one year” by Anna Judd

pokazukha

Posted in politics, tagged politics, Putin, Russia, the arts on 03/16/2010| Leave a Comment »

Who is Yury Shevchuk? I’ve never heard of him before. But then I’m in the U.S., and he’s back in the U.S.S.R….and we have nothing in common that I know of, except for a personal distrust of Putin’s politics. He is a rockstar, a Bono of sorts, who is using his fame to voice his opinion about the nasty aspects of the current administration.

Who is Yury Shevchuk? I’ve never heard of him before. But then I’m in the U.S., and he’s back in the U.S.S.R….and we have nothing in common that I know of, except for a personal distrust of Putin’s politics. He is a rockstar, a Bono of sorts, who is using his fame to voice his opinion about the nasty aspects of the current administration.

Shevchuk said despite the fact that many musicians are co-opted by the regime, there is also a small revolution brewing below the decks. He compared the situation to the underground Soviet rock scene in the 1970s and 1980s: ‘I know there are thousands of wonderful musicians who sing songs about civil themes, who do not agree with what is happening in this country. There are a lot of wonderful young people who are playing in cellars. And all this is gaining some critical mass.’

And what of “pokazukha“?  It’s a Russian word meaning “for show” or “counterfeit” or “simulated”. It’s something Shevchuk’s passion is not.

It’s a Russian word meaning “for show” or “counterfeit” or “simulated”. It’s something Shevchuk’s passion is not.

Will these nascent, scattered, and fractured roots of a social uprising reach critical mass and become a catalyst for real political change? Will they get crushed in a Kremlin crackdown? Or will it all fade away, leaving people discouraged and disgusted? Stay tuned.

–Based on an article by Brian Whitmore.

everything you always wanted to know about butoh….. but were afraid to ask

Posted in A & E, tagged Butoh, culture, dance, foreign, Kyoto Journal, modern dance, performance, the arts on 01/18/2010| Leave a Comment »

based on the article Dance Kitchen by Dustin W. Leavitt; Kyoto Journal

.

.

Having never seen the Asian dance form called “Butoh”, it is interesting to hear how it might be explained verbally, rather than visually. One might as a comparison, try to describe the movement known as “ballet”, and compare it to “modern dance”. One might compare mime to Mummenschance, and Olympic floor routines to Cirque du Soleis. Personally, I feel that Cirque has more to do with costume and theatrical calisthenics, than choreographed dance.

But all the aforementioned forms of performance art, are created and to be decoded by the western mind. Butoh originates in Japan, and must be interpreted through eastern culture. Visually westerners may see and interpret the form, but they may not understand the cultural significance. According to Dustin Leavitt, Butoh is

strange, dark dance form created by Hijikata Tatsumi in Japan during the years following World War II. Critic Mark Holborn has written that butoh is defined by its very evasion of definition. “Hijikata’s dance was literally called Ankoku Butoh,” he said, “meaning black or dark dance.

The darkness referred to elements — the territory of taboo, the forbidden zones — on which light had never been cast… It is both theater and dance, yet it has no choreographical conventions. It is a subversive force, through which conventions are overturned. As such, it must exist somewhere on the social periphery… It is a force of liberation, especially within the conformist Japanese social structure…”

Ahhh…the “social periphery”? Something which overturns conformist Japanese social conventions?

Later works were heavily invested with transvestitism, sexual perversion, and violence, the purpose of which was not to comment, nor even to shock, though that was often their effect upon the audience. Rather, they were enlisted as means of undermining the barriers of convention that held the body in thrall.

Located at the heart of darkness, violence and sexual perversion were Hijikata’s Jacob and Angel, whose true struggle was not against each other, but rather against the authority that manipulated them both; they were the keystones whose removal into the light of scrutiny would cause the vaults of the unconscious to sunder.

Well speaking generally, ballet as a genre didn’t tend to violate social conventions. In fact, it’s formalism was breached by dancers who pushed western boundaries, such as Nijinsky, bringing chaotic and passionately liberated modernism to dance. In his time, Nijinsky was seen as shockingly different than what staid and conservative audiences were used to. His dance “Rite of Spring” broke it’s own social conventions, ushering in new and freer forms of movement. So Butoh’s Hijikata would seem to be the Asian analog.

During the early years, when Hijikata worked with Ohno Kazuo — who is credited with butoh’s co-creation — Ohno’s son Yoshito, Kasai Akira, Ishii Mitsutaka, and Tamano Koichi, butoh was an essentially masculine dance form. In the early 1970s, however, he began to work with three women, Kobayashi Saga, Mimura Momoko, and Ashikawa Yoko. Hijikata’s collaboration with Ashikawa was transformative. Through her he investigated the practice of metamorphosis as

a gentler means of breaking down the myth of the individual, the first step in the process of reintegrating the body with its analogous exterior and interior universes. He led his dancers through exercises, sometimes lasting years, in which they assumed other life forms — animals, plants — with the objective of exchanging the isolation of individuality for a sense of communion with nature, of infusing the subjective body with firsthand experience of adapting itself to its place in the natural order.

Most similar to the western concept of modern dance, in its movement free of formality, Butoh differs to the extent it’s participants engage in more meditative immobility–something that westerners, used to a barrage of visual stimuli and bold action, find more difficult to accept as entertainment.

And yet, what is “butoh” as compared to other dance? Perhaps it is more the expression of the individuals.

“Butoh is dancing,” she says reflectively. “Butoh is dancing… stomping on the ground.”

Hijikata’s ankoku butoh sought, through the body, to access a liminal, pre-Babel world where the relationship between sign and signifier is not separate, but motivated, a world described by critic Eguchi Osamu as one in which all hierarchical relations fragment and are replaced by a “mandala woven from words and resemblances which, as it swirls around, creates correspondences between all things.”

“It’s so straight!” Hiroko continues. “All dance is the same. With butoh we are kind of making a new genre, but the unique point, or the most important part of this dance form, I think, is what really makes that form…

You know, the dance sometimes just forms and forms and forms and then space. Like, sculpted the body out to the shapes, but the point is: how come those shapes comes out? Anno, what makes you run? What makes you cry? What makes you laugh, and all those things. And how come this hand moves this way and not this way? You know, those inside things.

“And also, you know, the human body have that same space as outside universe. So individual people have that same universe inside. And all the vocabulary, already there. Everybody has all that vocabulary already.”

She gives me a hard look. “We has eyes to see around, but sometimes we forgot to see inside.”

I guess I’ll just have to see it. 🙂